Air quality index (AQI), according to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), is a measure of the concentration of eight pollutants — particulate matter (PM)10, PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), ozone (O3), ammonia (NH3), and lead (Pb) — in the air at a monitoring location. A sub-index is calculated for each of these pollutants (not all may be measured at every station); and the worst among them is the AQI for that location. So, AQI transforms complex air quality data into an index we can understand.

Also Read:Clearing the air on Delhi’s pollution crisis

How uninhabitable is Delhi?

Delhi is perhaps going to become, if it has not already, an uninhabitable city for two different reasons. In winters (October-February), pollution levels peak, while during summers (April-June), the heat waves are unbearable, both affecting Delhi’s poor disproportionately. This piece concerns itself with air pollution. This article will focus on the PM2.5 in particular because it dominates the AQI reading in Delhi and is quite dangerous as it is likely to travel to the deeper parts of the lungs owing to its extremely small size, the largest of which is 30 times thinner than human hair.

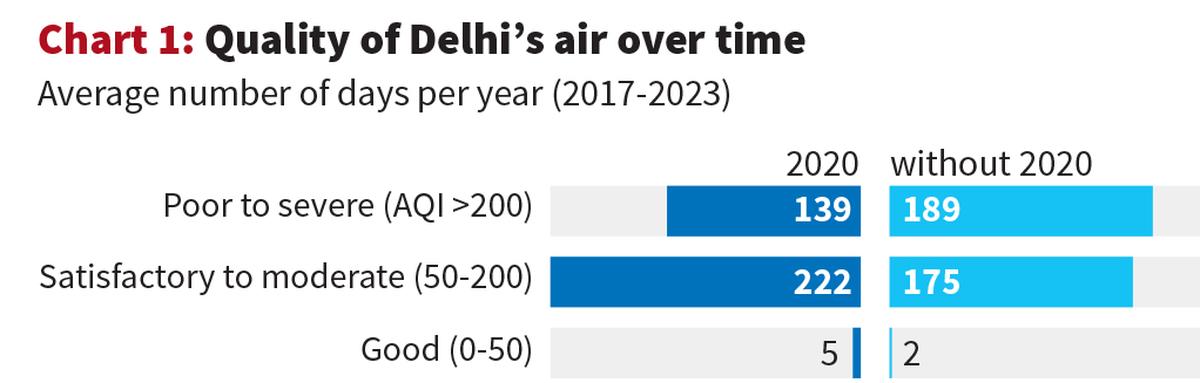

Chart 1 shows how the quality of air has been over a period of seven years (2017-2023). AQI is categorised in six ranges in India. We have combined some of them to represent as: good (0-50), satisfactory to moderate (51-200), and poor to severe (201 and above). A few things stand out. One, Delhi has had only two days of healthy air per year. Two, more than half a year people are inhaling air unfit for breathing. Three, and quite remarkably, even for 2020, a lockdown year, things were only marginally better. It’s clear there is something systemically wrong with the system.

Why is Delhi’s air quality so poor?

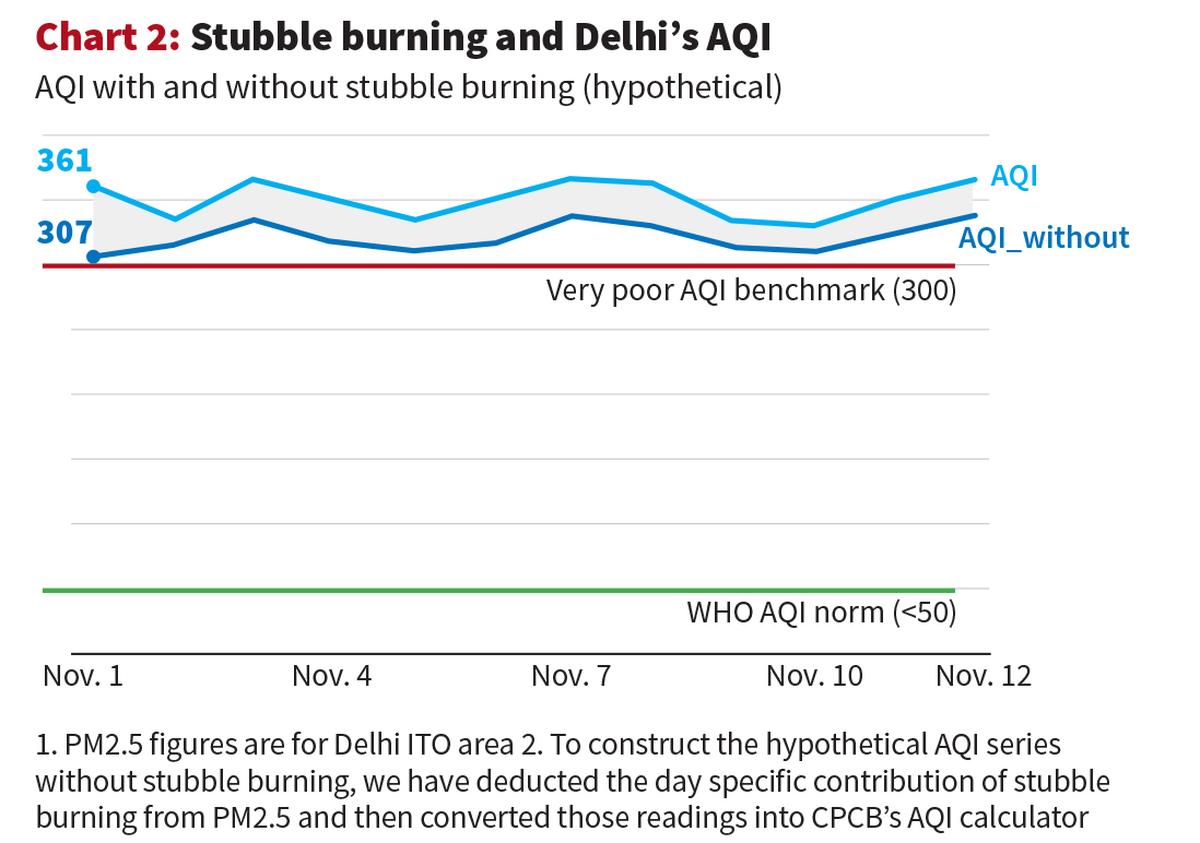

The government often tells us that stubble burning in Punjab, Haryana, and U.P. is responsible for Delhi’s pollution. It’s a half-truth. We pick the most intense days of November this year when stubble burning’s contribution to PM2.5 has been at its peak (in the range of 15-35%).

Chart 2 plots the actual AQI against a hypothetical scenario of zero stubble burning, and the result is startling. Not even on one of these days would the AQI have fallen below the very poor AQI benchmark (300). This exercise is not to downplay the role of stubble burning. It is to show that it is a red herring used by the two warring political parties, one which runs the Union Territory and the other this country, to avoid acting on the problem in any serious manner.

What are the factors contributing to the AQI other than stubble burning?

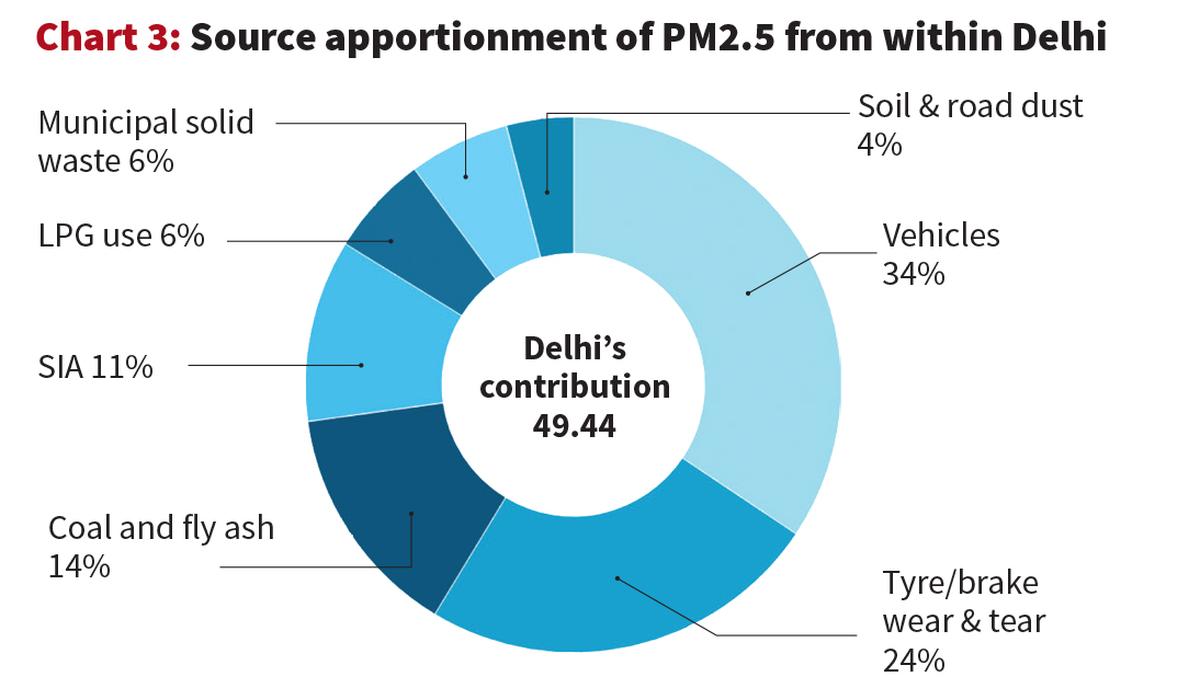

An extensive 2023 report prepared by IIT Kanpur, IIT Delhi, TERI New Delhi, and Airshed Kanpur shows that, even during winter months, when sources of pollution external to Delhi are at their peak, half of the PM2.5 levels can be apportioned to Delhi itself (Chart 3).

Vehicles alone contribute 58% — 34% from the exhaust and 24% due to wear and tear of tyres/brakes — to this total. The only realistic solution to air pollution is a massive shift in the way Delhi travels, that is, from private (cars and motorcycles) to public transport running on cleaner energy, with last mile connectivity, a step which will bring the number of vehicles on the road down significantly.

Why are the winters so much worse?

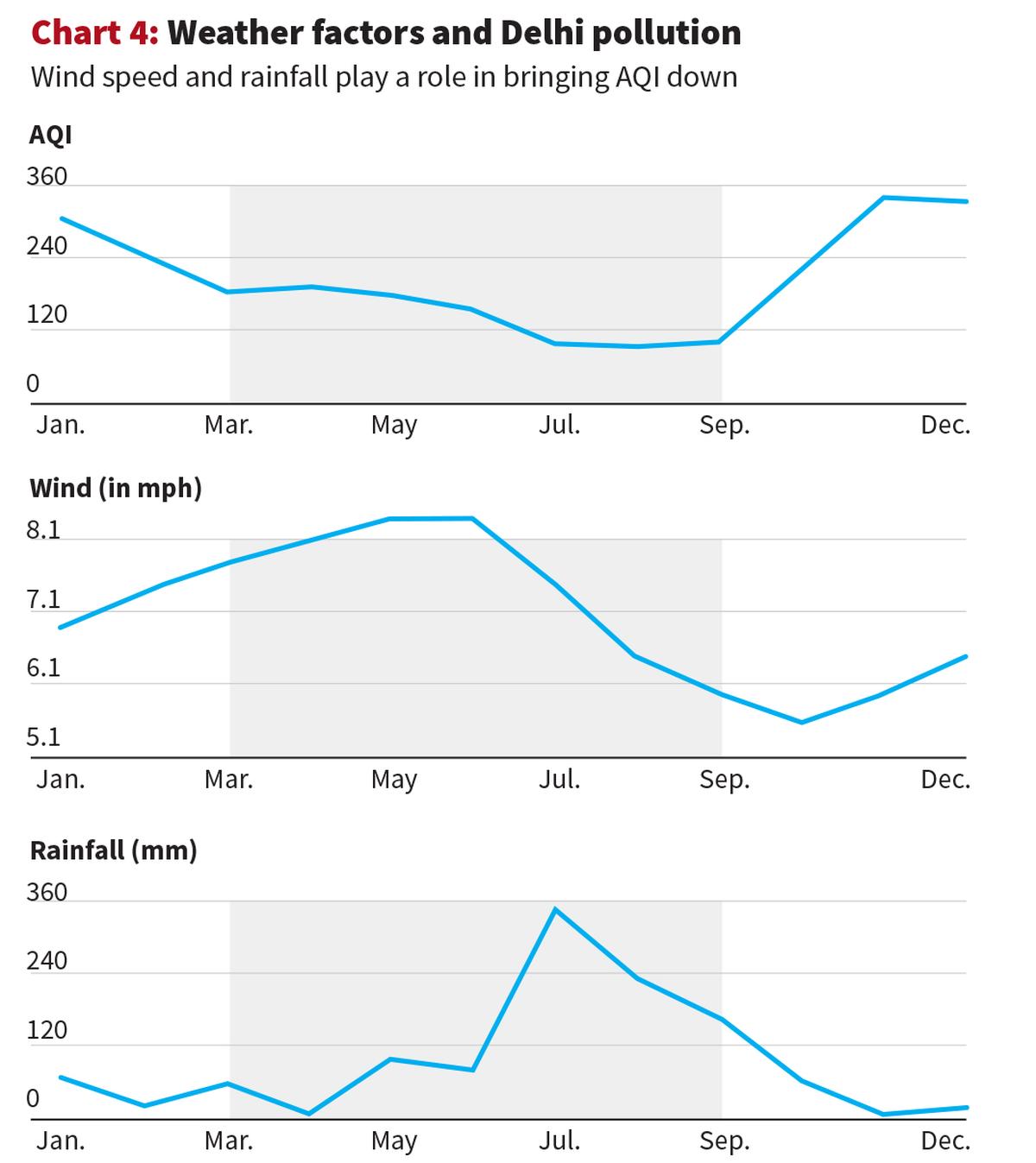

The concentration of pollutants in the air depends not just on emissions but also on many meteorological factors — temperature, wind direction/speed, and rain, among other things. Hot air, being lighter, moves up (thereby carrying the pollutants with it), whereas cold air traps pollutants and keeps them closer to the ground. Similarly, wind can disperse the pollutants, while rain can force the most common air pollutants, like PM2.5 and PM10, to the ground. Cold air with slow wind speed and no rains make Delhi a pot of pollution with a lid on.

Chart 4 shows that for the months which have a moderate AQI, either the wind speed is relatively higher (February-June) or rainfall is greater (July-September) than the rest of the year. Both these factors, aided by warmer air, lift the air quality of Delhi from poor/severe to moderate. Given that Delhi’s own emissions are not winter-specific, its air quality would have been poor throughout the year but for these favourable factors from March through September.

What is the impact?

According to the WHO, ‘almost every organ in the body can be impacted by air pollution’ and some air pollutants can enter the bloodstream via the lungs which can lead to systemic inflammation and carcinogenicity.

Also Read: Air pollution in Delhi over 26 times the limit prescribed by WHO

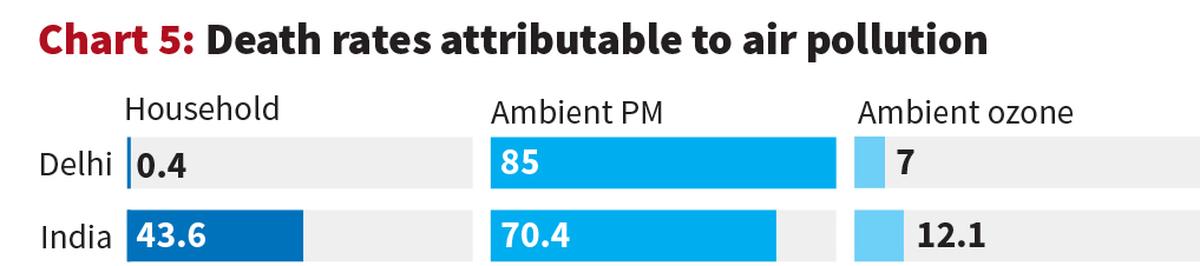

A study in the Lancet Planet Health journal shows that, in 2019, an estimated 1.67 million deaths in India were attributable to pollution, and one out of 10 deaths were caused by ambient particulate matter (PM) pollution. The study categorises the deaths attributable to ambient PM, household, and ambient ozone pollution. Chart 5 contrasts the death rates (number of deaths per 1,00,000 population) at the all-India level with those of Delhi.

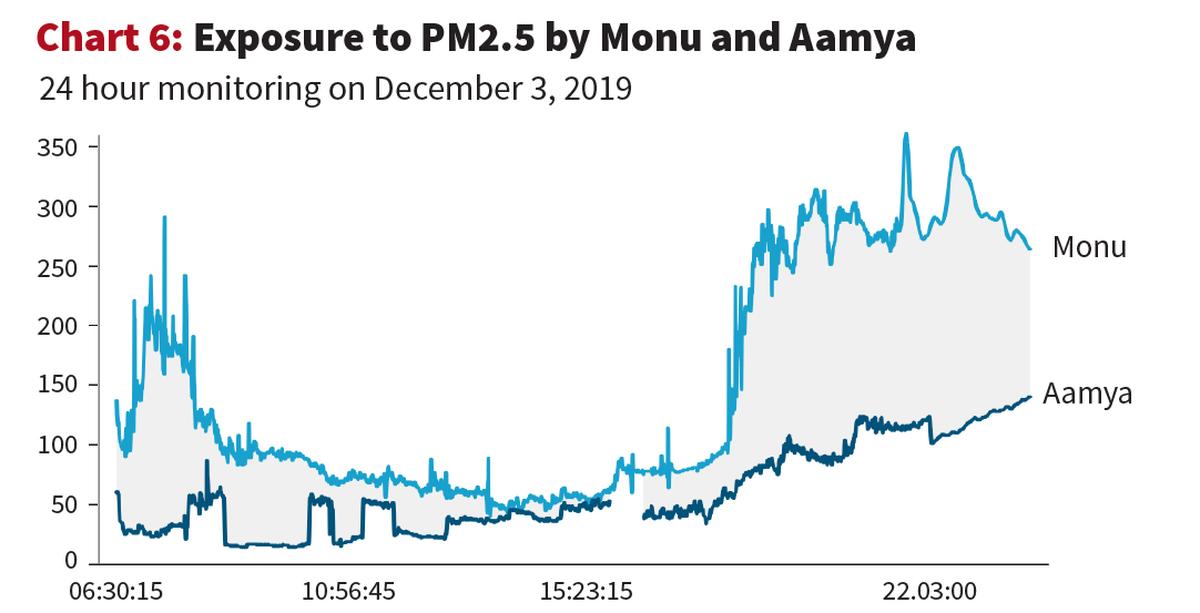

While Delhi’s death rate attributable to household pollution is negligible in comparison to the Indian average, it is higher than the Indian average for ambient PM pollution, which reiterates the unhealthy levels of persistent exposure to PM2.5 and PM10 one has throughout the year. More importantly, this health impact is not undifferentiated across class. The poor and the marginalised suffer disproportionately more than the others. Based on a photo/data essay in the New York Times, Chart 6 plots the real-time exposure to PM2.5 for two similar-aged children in Delhi, Monu, who comes from a poor neighbourhood across the Yamuna and Aamya who comes from a more affluent family living in Greater Kailash.

The shaded area between the two lines in Chart 6 is the class gap to pollution exposure. With some simplifying assumptions, the article argues that this kind of consistent exposure over a long term could shorten Monu’s life by around five years, compared to Aamya (whose life expectancy also gets shortened). Children whose lungs are still developing get adversely affected, and within those, poor children lose much more than their more affluent counterparts.

Calling Delhi a gas chamber is, therefore, definitely not an exaggeration. Surely, we don’t want our kids (or residents in general) to lose precious years of their lives because of what is a controllable problem. But it requires a political will and an imagination. Stopgap measures of odd-even, red-light on engine-off, water sprinklers every winter by the AAP government, which has now been in power for almost a decade, or distribution of masks by the BJP are mostly measures aimed at media management, which will have little to no impact on the problems at hand. The Modi government, by shifting the blame on the AAP government without taking any proactive steps itself, shows its absolute lack of sensitivity to the well-being of the citizens, including those who are based in the city.

Rohit Azad is a faculty at the Centre for Economics Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Shouvik Chakraborty is a Research Assistant Professor at the Political Economy Research Institute, Amherst, U.S.

Published – November 22, 2024 08:30 am IST