On the morning of November 2, on a hillock adjacent to Uliyana village, the rhythmic bleating of goats suddenly went silent. Over the next few hours, the village, situated in Rajasthan’s Sawai Madhopur district, witnessed the discovery of a corpse, flying axes and improvised low-intensity devices, a protest, and later in the night, the carcass of a 12-year-old tiger.

Bordering the over 1,500-square-kilometre Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, the village has often seen Royal Bengal Tigers descend from forested hillocks to the low-lying agricultural fields in search of easy prey like cattle. However, on that Saturday, the tiger was allegedly found sitting next to the mauled body of a villager, Bharat Lal Meena, 50. The tiger had one paw on the corpse, say villagers. Later, he was identified as Chirico, or T-86, the Forest Department’s ‘file name’ used for tracking purposes.

According to government data, from 2019 to 2024, five human beings have lost their lives in tiger attacks, and over 2,000 cattle were killed by tigers in the same period. While the Forest Department records the number of tiger-related deaths, there is no record of them being killed.

A few days after the incident, there were reports in the media about the Forest Department recording that 25 of Ranthambore’s 75 tigers were “missing”. Officials clarified that 14 tigers had been missing for less than a year; 11 for over a year. An official says there could be many reasons for this: tigers not caught in the monitoring cameras, migration, death due to old age, and even poaching. Soon, 10 of the 14 were tracked. The National Tiger Conservation Authority, which conducts a tiger census every four years, has asked the Wildlife Crime Control Bureau to look into the matter.

A village mourns

In Uliyana, a shroud of grief surrounds the newly constructed house of Bharat Lal’s family. Prasathi Meena, his wife, is surrounded by women relatives in one corner of the house. “There was a lot of commotion; then someone said my husband had been attacked by a tiger. What happened after that is a blur now,” says Prasathi in a hushed tone from beneath a ghoonghat (veil) that covers her face and neck.

Prasathi, who villagers say fainted seconds after receiving the news, recalls that her husband had stepped out to take his goats to graze in the buffer zone between the tiger reserve and their village. There are walls built around villages, but there are breaks, and many require repair.

“My husband would step out every day around 10.30 a.m. On that day too, he had his meal and left with the goats around noon,” Prasathi says, her voice drowning amid the heavy, synchronised wails of women mourning around her. She never imagined that the tiger would take him. “Why did the tiger not take the goats and spare him?” she says.

Prasathi Meena, whose husband Bharat Lal Meena was killed in a tiger attack, with her son at Uliyana village in Rajasthan’s Sawai Madhopur district.

| Photo Credit:

Sabika Syed

Babu Lal, the sarpanch of Uliyana, who was at the forefront of the attempted rescue mission, recalls seeing the tiger sitting next to the body of Bharat Lal. “We weren’t sure what his condition was, but the chance of him surviving a tiger attack was slim,” he says.

The low-lying buffer zone, which separates the agricultural land of the village from the lush green tiger terrain in the hills, soon saw the rise of a mob. Instinctively, villagers threw tote (countrymade bombs used to break stones), axes, stones, and every sharp object they had at the tiger, Babu recounts. “I had called the Forest Department and the police, but they did not come immediately and we had to try and save our brother,” he says.

Chirico retreated into the forest and the villagers rushed to Bharat Lal, who had grievous injuries. Angry and frustrated at the lack of a proactive approach by government agencies, the villagers carried his body to Sawai Madhopur-Kundera Road, almost 5 km away.

“Over 1,000 people sat in protest on the road, blocking it for passers-by. The mob refused to hand over the body for post-mortem until the family was paid ₹15 lakh,” a senior Forest Department official says.

Twenty-one hours later, State Agriculture Minister Kirodi Lal Meena met the angry villagers on the road that connects villages in the district. “The villagers handed over the body and cleared the road only after the Minister assured them of compensation,” recalls the official.

Years of anger

This distrust towards the Forest Department officials is not new, says Dharmendra Khandal, a wildlife biologist with Tiger Watch, a non-profit organisation involved in wildlife conservation in Ranthambore. “Fateh Singh Rathore [who went on to become Ranthambhore’s Field Director] was attacked by the villagers of Uliyana in the 1980s. The villagers had broken both his legs. His life was spared only because his driver managed to come between him and the angry mob,” says Khandal.

Rathore, who founded Tiger Watch and is often called India’s ‘Tiger Guru’, was one of the members of the first Project Tiger started in 1973 to conserve tigers in the country. “The villagers were angry that they were being displaced by Rathore to give better structure to the tiger reserve,” Khandal says. The belief among villagers today is that the reserve is being maintained to attract international tourists at the cost of the lives of people who live in the forest, he says.

The day after Bharat Lal died, the Forest Department formed a search party to look for Chirico. “We could not enter the village as the residents were still agitated, and from what human intel we had received, the tiger was badly injured after he was attacked,” says the official.

The department sent drones around the forest bordering Uliyana and spotted the tiger’s carcass about 500 metres from the spot where the villagers had found Bharat Lal’s body. “Chirico has often preyed on cattle in the nearby villages but not on any human. Contrary to what locals are saying, he was not a man-eater,” he says.

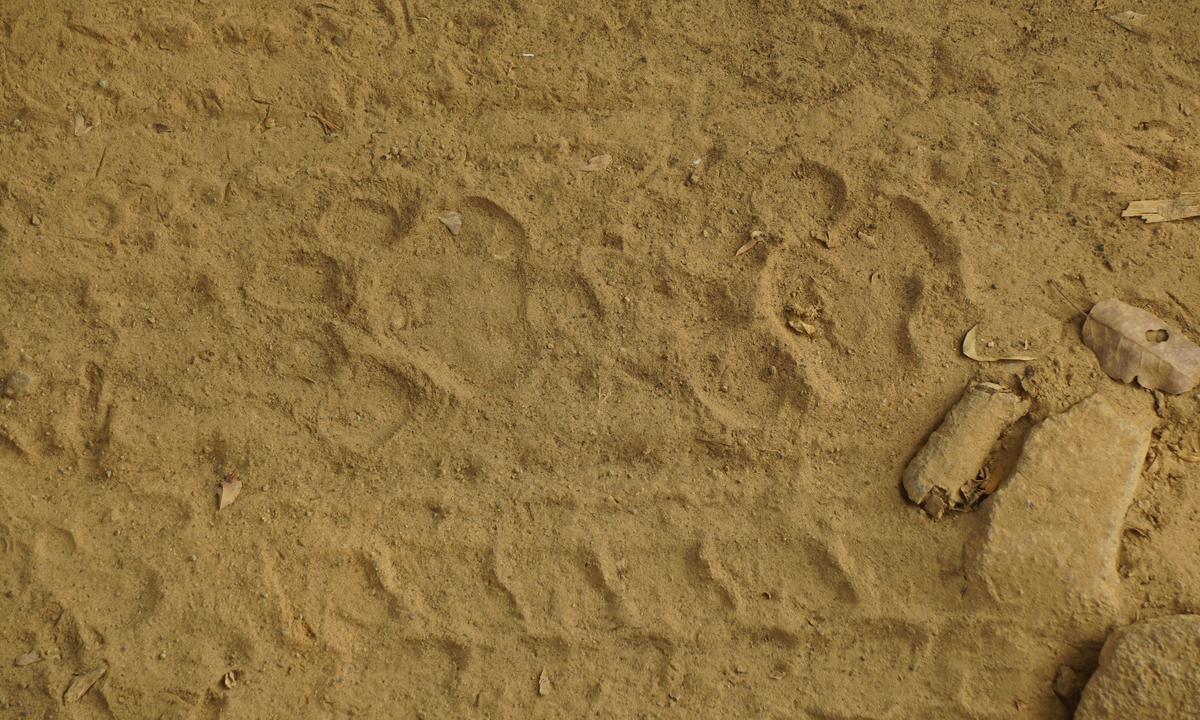

Pugmarks at Ranthambore Tiger Reserve, often used to track tiger movement.

| Photo Credit:

Sabika Syed

The official adds that the tiger had old injuries on his front legs and chest from a fight for territory with another tiger in the forest. “The post-mortem report has shown that those wounds were healing. He died primarily due to traumatic injury on his face and back from sharp objects,” he says.

A retired Forest Department official says contrary to the perception of the villagers, a majority of Ranthambore’s tigers are not man-eaters. “A man-eating tiger is one that has been compelled through stress of circumstances to resort to preying on humans,” the official says. These circumstances are usually beyond the tiger’s control. “Mostly wounded, old tigers resort to becoming man-eaters, but human beings are not their natural prey,” he says.

Anoop K.R., Field Director, Ranthambore, says it is possible that T-86 had wanted to attack the cattle, but since the man was a barrier, the tiger attacked him instead.

Changing patterns

Despite villagers coexisting with tigers and other wildlife in the area, increased human-animal conflict has forced people to make changes in their ways of living and working.

In Khava village in the same district, Bhatti Lal says his brother was mauled and killed by a tiger last year when he took his goats out to graze not far from the boundary wall that separates the village from the forest. “He was sitting in the hilly area while the goats were grazing. The tiger attacked him from behind and dragged him into the forest,” says Bhatti. Since then, the pastoralists in the area have started making loud sounds when they take cattle to graze, he adds.

Hanuman Meena, another resident of Khava village, says most villagers are selling their livestock at a loss. “A grown goat can be sold for more than ₹10,000, but now fearing for our lives, most of us are selling them at ₹4,000-₹5,000,” says Hanuman. This has also deprived them of a livelihood from dairy products. Most villagers in the area depend on growing wheat, jowar, or bajra. A few are employed in the tourism industry.

Cattle rearing communities around Ranthambore National Park are selling their goats and cattle in apprehension of its loss.

| Photo Credit:

Sabika Syed

News of Bharat Lal’s death also reached the neighbouring villages like Padli. Here, in 2019, a woman was attacked by a tiger while defecating in the fields. While in Uliyana and Khava, tigers had attacked villagers on the periphery of the forest, in Padli, Munni Devi was killed about 6 km from the forest area, say villagers.

According to her neighbour, Rekha Devi, tigers often roam in the village’s guava patches, but it was for the first time that it had attacked a human. “Then houses in the village did not have bathrooms, so women would use the fields, going early,” explains Rekha, adding that the incident took place at 5 a.m. Since then, women go in groups to defecate or work in the fields.

Villagers also complain that despite many representations to the Forest Department to increase the height of the boundary walls and maintain them, nothing has been done. “At least 30% of our crops are destroyed by wild animals (nilgai, brown bears, leopards). The cost of this is not met by the Forest Department,” says Ramesh Meena, a resident of Padli.

Ramesh adds that while the Forest Department is supposed to provide compensation of ₹5,000 to ₹10,000 for the loss of cattle, in most instances the hassle of travelling over 15 km to a government office many times, over a number of months, is more harrowing than bearing the loss. “Many villagers give up on the compensation,” he says.

Villagers living in the buffer zone say the behaviour of tigers over the past decade has changed. Laad Devi, 70, from Khava village, says tigers and humans have long coexisted in this area. “Tigers would wander about the fields in the early morning. They did kill cattle, but never attacked humans in this region,” she says.

Laad recalls one such day from her childhood when a tiger had made its way into her millet field. “It was a misty morning and when I spotted the tiger in the field, I just stood still. It passed by me and went towards the other end of the field,” she says.

Villagers and the retired Forest Department official say Ranthambore is overcrowded with both tigers and humans. Tigers in the area have historically migrated to Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, but of late outmigration has been negligible, they say.

Published – November 22, 2024 01:11 am IST